The Bicycle Craze Part 2

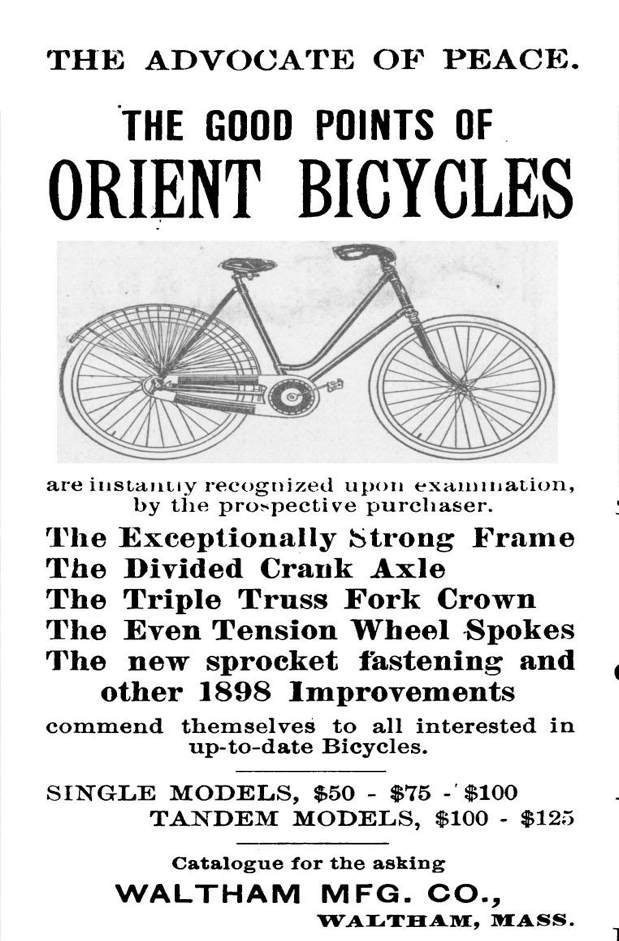

During the height of the bicycle craze in Waltham, crowds between ten thousand and fifteen thousand flocked to watch the racers, both solo and tandem. Many of these racers rose to fame on the seats of Orient bicycles, manufactured locally in Waltham by Charles Metz. Orient bicycles, produced at the Waltham Manufacturing Company, were some of the most popular and state-of-the art machines available for racers and leisure riders. In an overview of bicycle racing as the sport of the moment, one historian refers to the Orient as one of the “hot, fast bicycle names.”[11]

Before narrating Charles Metz’ contributions toward bicycle production and innovation, it’s useful to have some background on the origin of the bicycle itself. By all accounts, it began with German inventor Karl Drais. In 1818, he created a machine with two wheels a steering column, and a padded seat. The running machine was known in English as the Draisine (an eponymous name).[12] Farmers would cross fields, using their legs and feet to propel the machine forward--faster than walking. Also referred to as the velocipede, many from Europe and America rode this novel machine, but found it impossible to keep their balance on rutted roads.[13]

While the Draisine’s popularity was short-lived, it captured the public's imagination, indicating an incipient demand for two-wheeled propulsion. After the Draisine, French inventors designed a velocipede which many consider to be the forerunner of the modern bike. Either Pierre Michaux or his son Ernest attached pedals to the front wheel, using cranks to convert more energy to the machine, while lifting the cyclist's feet off the ground. As importantly, this velocipede was the first to be mass produced, made possible by shifting from wood to cast iron. Known as the “boneshaker,” it also made for a very painful ride on rutted, dirt roads. Designed in the early 1860s, the “boneshaker” found itsconverts among leisure riders and racers, but it did not survive this decade.[14]

In 1870, the high-wheeled “Ordinary” arrived on the scene (also known as the Penny-Farthing). While awkward and dangerous to mount and dismount, with its fine-tuned gear ratio, rubber wheels, and relative lightness, it was one of the most comfortable and swiftest rides thus far. Despite the risks, these were the first bikes to be pedaled cross-country and to be raced for speed records around the globe.[15] In fact, Charles Metz joined the ranks of bicycle enthusiasts and in 1885 became the highwheel champion of New York State, at the State Fair, in Syracuse.[16]

Born on October 17, 1863, Charles H. Metz was the son of a “high-grade mechanic,” involved in “contracting and building business” in Utica, New York.[17] An autodidact (only schooled through the sixth grade), Metz, according to one biographer, apprenticed to his father in carpentry.[18] He would later take a job at Orient Fire Insurance Company; and, while he left this business after a few years, he recycled the Orient name for his own line of bicycles in Waltham, Massachusetts. His love of the bike, combined with his talent for mechanics, inspired him to go into the bicycle business. As early as 1883, he served as an agent for Columbia bicycles, in his hometown of Utica. Even before he opened up his own factory in 1893 (The Waltham Manufacturing Company, Rumford Avenue), he worked as a designer, making parts for Union Cycle Company in Newton Highlands.[19]

His mechanical background, combined with his experience as a racer, motivated Metz to design lightweight, high performance racing machines, and amateur bikes, as well. By this point the “safety bicycle” replaced the highwheelers, and boasted wheels of the same size, pneumatic tires, and chain power distribution, not so unlike bicycles of today.[20] The opening of the Metz factory coincided with this wave of bicycle mania, and Metz produced everything from elite racing bikes, to tandems, to “Dainty” bikes for girls and boys.[21]

His invention of a stronger and lighter fork crown, and the production of lighter sprockets by removing unneeded metal through circular cutouts, helped to improve the performance of racing bicycles, and“led to speed records,” and great success for his teams and bicycles.[22] One model included the “Major Taylor”[23] bar extension, a drop handlebar, and smaller wheel, all designed to enable the rider to tuck in elbows, bend over, decrease height, and thereby reduce wind resistance. These ‘Mile-A-Minute’ models weighed just over twenty pounds (lightweight even by today’s standards) and paid tribute to Charles Murphy, who clocked a mile in minute in 1899.[24]