The Bicycle Craze Part 3

“Mile a Minute” Murphy drafting a locomotive

Murphy, a short distance racer, pulled off a daring and nearly life ending stunt by drafting (reducing air resistance by following another vehicle in its wake) behind a locomotive steaming at sixty miles a hour. He managed to match the pace and, after several tries, clocked a mile in under fifty-eight seconds on June 30, 1899.[25] On this last effort, he crashed into the rear coach of the train, and had to be lifted up bike and all into the back compartment.[26] He earned a nation-wide reputation for this both daring and perhaps foolish endeavor. Afterall, he nearly reached seventy miles an hour on that ride--imagine the fascination with a bicyclist who rode faster than a train: “Men and women were said to have fainted at the news” of Murphy’s performance.[27]

While Murphy did not race on an “Orient” bike, several acclaimed racers of the period did: “Frank (Dutch) Waller won several six-day endurance contests and the twenty-four-hour title.”[28] Fred Drew, another racer, was heavyset and became an “effective advertisement,” for the “strength of the Orient Wheels.” Other famous racers included Jimmie Michael, Harry Elkes, and Major Taylor; the latter two I will discuss below because of their preeminence in the world of racing.

Harry Elkes, (born in Glen Falls New York, 1879), was “a physical marvel,” so proclaimed the Chicago Tribune in 1900. On December 22, 1900, he won “the hardest six-day race ever run in the country.”[29] During this highly competitive trek, one cyclist “met his death,” another became dangerously ill, and Elkes’ partner could barely walk afterward.[30] Just five days after this race, Elkes set a new indoor record for the mile, pacing behind a motorcycle, he clocked the mile at 1:36. On May 30th, 1903 (four days before retiring), Elkes, at the Charles River park in Cambridge, crashed into a motorcycle pacer, injuring two others, and killing himself in the process. Nearly a year before (June 12th), Elkes broke the hour record by an entire mile (shattering the previous 41 miles, 250 yards), setting an unassailable world record.[31]

Another Orient rider of great acclaim faced not just the time barrier, but the race barrier, as well. His records are only surpassed by his willingness as an African-American to compete in races throughout the country. Of course, he was barred from the South. Major Taylor raced Orient bikes for the Metz Waltham Manufacturing Company, and between 1897 and 1900, he was the fastest sprinter if not the fastest rider in the United States. His unparalleled sprinting ability allowed him to shoot past the field into a winning position, a great crowd pleaser, and probably one of the reasons he was allowed to race at all. Not only did he face regional prejudice but other racers tried and were at times successful in injuring him during a competition. Once someone attempted to choke him to death at the finish line. That Major Taylor raced for Orient bicycles granted him ephemeral status and legitimacy in a violently racist world.

19th Century African American athlete Major Taylor

Orient bikes may have made an even greater name, with its famous riders and lightweight machines, had Metz not shifted to car manufacturing. The American Manufacturing Company produced approximately one hundred thousand bicycles between 1893 and 1902. But by 1909, the Metz Company (car manufacturing) was incorporated, and Charles Metz would soon become its president.[32] Though one might be saddened by Metz’ departure from the bicycle scene in the latter part of the first decade of the twentieth century, bicycling as a whole declined, and the only vestige of this amazing age was the child’s bike and trike. The adult recreation and racing bicycle would enjoy a resurgence over half a century later during the recreation revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. Several factors influenced the bikes decline in the early twentieth century: the monolithic rise of the car for everyday use and racing during the first two decades of the twentieth century; the rise of basketball and football as new spectator sports and severe cuts in bike production during the Great Depression.[33]

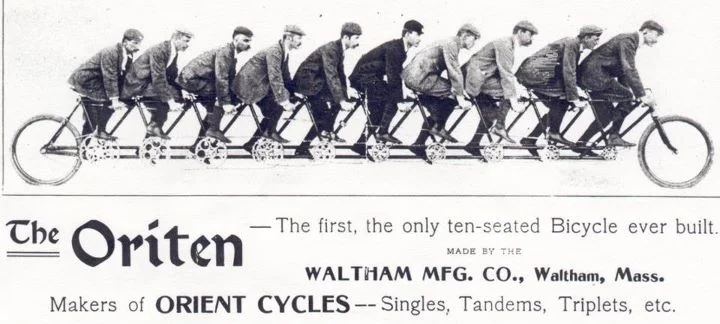

At 23 feet in length and 305 lbs., Charles Metz's "Oriten" was built purely for promotional purposes. The bicycle is now part of the collection of the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan

End Notes

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Augustus_Zimmerman

[2] http://www.angelpig.net/victorian/cycling.html

[3] Peter Nye,Hearts of a Lion: The History of American Bicycle Racing, W.W. Norton & Company, New York and London, 1988, pg. 33.

[4] Todd Balf, Major: A Black Athlete, A White Era, and the Fight to be the World’s Fastest Human Being, Crown Publishers, New York, pg. 2.

[5] Major, pg. 2

[6] http://americanhistory.si.edu/ontime/

[7] http://hubtrotter.blogspot.com/2009/06/when-waltham-was-hub-of-cycling.html

[8] http://hubtrotter.blogspot.com/2009/06/when-waltham-was-hub-of-cycling.html

[9] http://hubtrotter.blogspot.com/2009/06/when-waltham-was-hub-of-cycling.html

[10] Frederic L. Paxson, “The Rise of Sport,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Sep., 1917), pp. 143-168.

[11] Todd Balf, Major: A Black Athlete, A White Era, and the Fight to be the World’s Fastest Human Being, Crown Publishers, New York, pg. 2

[12] Or, in German, the Laufmaschine

[13] Velocipede was a term used for human powered two-wheeled machines of any type, until supplanted by the term bicycle around 1869. See, http://amhistory.si.edu/onthemove/themes/story_69_2.html

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Michaux, Barton, Samuel M., “The Evolution of the Wheel: Velocipede to Motocycle,” The Sewanee Review 5 (1), 1897.

[15] http://amhistory.si.edu/onthemove/themes/story_69_2.html

[16] Daniel U. Holbrook, “The Metz Company of Waltham: A Contextual History,” (Senior Honors Thesis, Brandeis University, 1986), p. 69.

[17] Edmund L. Sanderson, “Waltham Industries: Am Collection of Sketches of Early Firms and Founders,” (Pamphlet, Waltham Historical Society in cooperation with The Waltham Chamber of Commerce, 1957.), p. 78.

[18] “The Metz Company,

[19] Sanderson, “Waltham Industries,“The Metz Company of Waltham, “ pg. 78.

[20] “The Metz Company,” pg. 69.

[21] Orient Cycles Catalogue,Providence Albertype Co., Providence, Rhode Island, 1897, pp. 5, 12, 14, 15, 18-19.

[22] “Metz Company,” pp. 68-70.

[23] Marshall Taylor was one of the fastest cyclists of the era.

[24] “Metz Company,” pg. 71.

[25] http://www .bikereader.com/contributors/woodland/murphy.html

[26] Hearts of Lions, pp. 29-32

[27] Hearts of Lions, pg. 32

[28] “Waltham Industries,” pg. 79.

[29] Six-day races were run continuously around a velodrome track. Towards the end of these races, cyclists fell of their machines, hallucinated, etc. These were very dangerous endeavours risking the health and life of the competitor.

[30] http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1900/12/24/page/8/article/harry-elkes-a-physical-marvel

[31] The Automobile Review, June 15, 1903, pg. 232.

[32] “Waltham Industries,” pp 79-81

[33] Hearts of Lions, p. 13