Of Trenches & Timepieces

Wartime effects on the Waltham Watch Factory (1850-1865).

By Amy Green, Ph.D., Charles River Museum historian

Listed under the state and national registers of historic places in 1989, the Waltham Watch Company revolutionized modern manufacture, attracting visitors from all over the world. Like its predecessors, the textile factories in New England, it mass produced all aspects of production under one roof. But in comparison to textiles, this was nothing short of a miracle given that watches were made up of over 160 miniature, moving pieces. Mass production supplanted the former cottage industry, hand assembling parts at different locations–an imprecise and time consuming process that produced a very expensive finished product. The factory also introduced precision machines (heretofore used primarily in gun manufacture) to forge miniature parts for the watch movement. They used fairly advanced assembly line methods to piece together the watch as a whole. This investigation of watchmaking and modern manufacture will highlight the themes above, but especially it will discuss the economic vulnerability of this enterprise in the 1850s and its surprising reprieve during the Civil War.

In 1850, Aaron Dennison, a watchmaker from Boston, wanted to establish watchmaking on a large-scale. He envisioned a Boston-based factory with global leadership, one that abandoned traditional methods, maintained a standard of excellence, and produced a variety of watch types, at a lower cost. First located in Roxbury Massachusetts, and operating under many different names, the factory finally found its home in 1854, purchasing vacant farmland by the Charles River in Waltham, Massachusetts.[1] By 1885 the name of the factory was changed from the American Watch Factory to the American Waltham Watch Company, and was renamed the Waltham Watch Company in 1905. Riddled with both successes and failures, the company struggled to maintain profitability throughout its existence, and was especially vulnerable to market volatility during the 1850 and 1860s.

Still, its achievements made it a leader in the Industrial Revolution: a mass produced timepiece boasting a level of precision outshining all watchmaking world-wide. This major innovation in watchmaking was made possible by the invention of automatic machines, designed to produce watch parts with great efficiency, eliminating, as mentioned earlier, the craft production of watches. Waltham’s greatest achievement to which other businesses and manufacturers aspired was standardization in all processes processes of production: 1) standardization of the actual watch parts, which I will discuss in more detail below, and 2) standardization of the actual assembly process, bringing efficiency into the movement and motions of each laborer, technically referred to as the division of labor—dividing labor into efficient units requiring only one or a few, repetitive tasks—anticipating the modern assembly line.

The idea to adopt a process of manufacture, (whereby the miniaturized pieces for the watch could be produced by machinery), and where watches could then be mass produced was radical in its reach. Dennison, youthful and idealistic, was the watch repairman who first put this idea into practice, and was joined in his efforts by three investors from Boston. Dennison introduced and applied the concept of “standardized, interchangeable parts.”[2] Of great inspiration to Dennison was the Springfield Armory, where he was a regular observer—here parts for rifles were so “identical in form and dimension” that they could be interchanged between any gun model.[3] No longer having to specialize each part for each product, interchangeability cut costs, increased efficiency, and overall precision of the final product. When applied to the machining of watches, unfortunately, the parts were not always interchangeable, and each watch had unique errors that had to be fixed.[4]

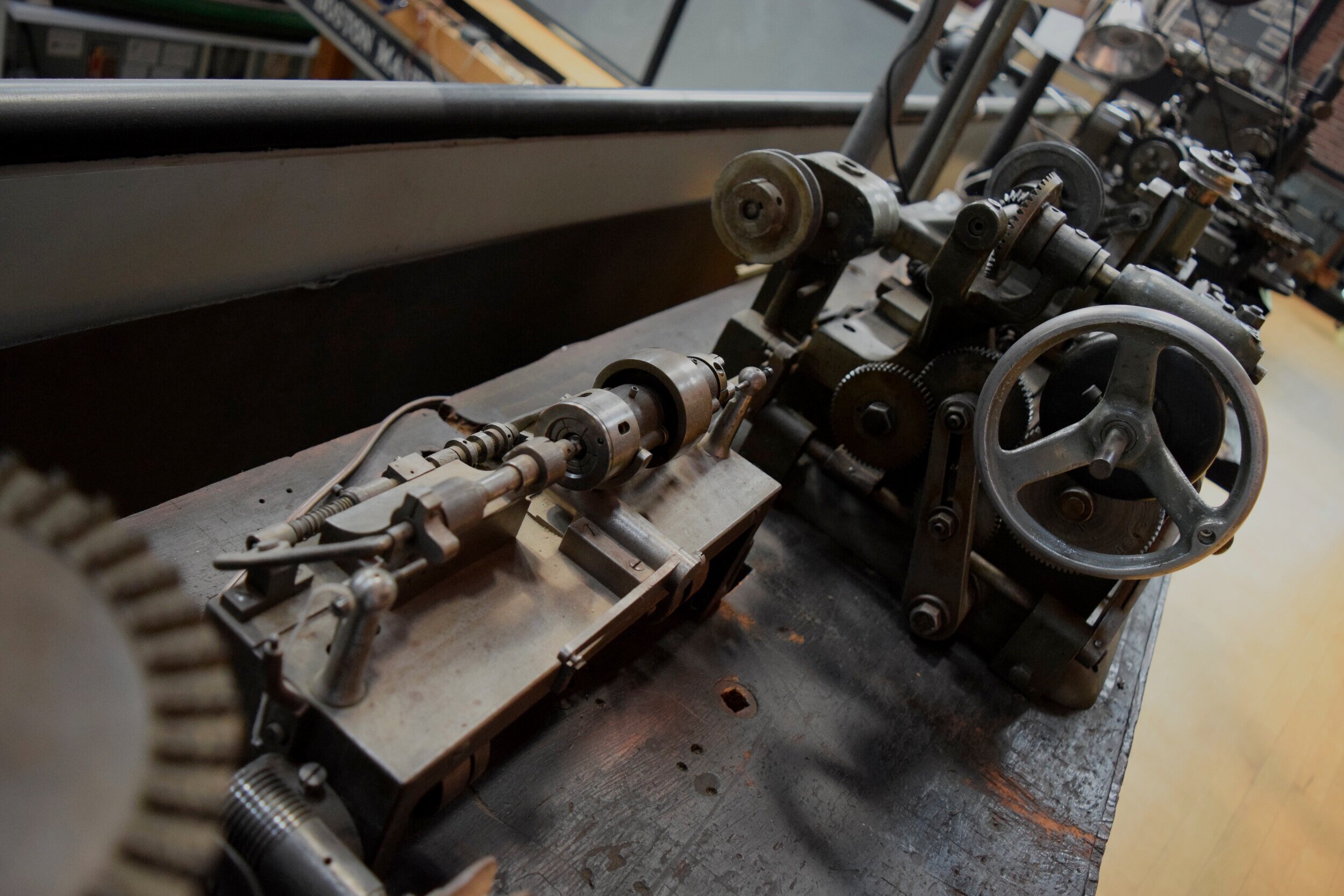

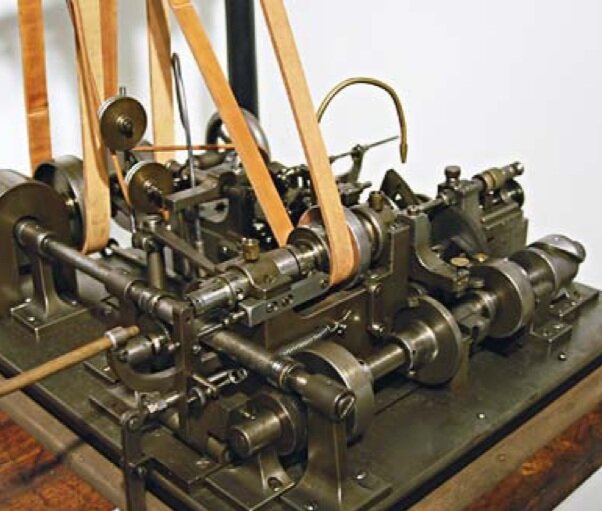

Notwithstanding the early shortcomings of interchangeable parts, the machining improved over time, and despite the obstacles mentioned above, machining led to a superior watch, for handwork could never match machine work in precision and quantity. For example, Charles Vander Woerd’s Automatic Screw Machine, pictured here (and see video below), made highly refined, miniature screws. One operator might attend over six of these machines, producing fifty to sixty thousand screws a day. By comparison, using older methods, a watchmaker with the help of an assistant might make up to fifteen hundred screws in a day, maximum.

The Waltham Watch Co. Automatic Screw Machine

By 1884, the factory in Waltham had produced over two million five hundred watches! Waltham employed as many as two thousand, four hundred laborers, a jump from their earliest figure of seventy five. And, by 1890, Waltham Watch Factory delivered “nearly twenty-two hundred finished movements” per day.[5] The American System of Manufacturing, whereby machines made machines, was taken to a new level at Waltham—so much so that legend has it that the Swiss, and automobile manufacturer Henry Ford, among other individuals and groups, came to view the miracle of the machined made watch. Of interest to Ford was the streamlining of the workplace, generating more out of each worker than previously known, an inspiration to his famed assembly line process. While the Swiss came to the factory to observe and learn about the making of precision watch movements.